Transness is everywhere, but where are trans people?

Preface: I wrote this essay for a zine I’m working on about queer and trans zines (QT zines hereafter) and politics. This piece will be out as a stand-alone zine at Spartacus Books and addyesusnick.com on the afternoon-ish of the 31st. The giant zine it’s part of will be out in print only in late April (or in your email inbox before WPSA, if you’re one of my co-panelists).

Thoughts on TDOV, Anti-Trans Media, and Zines

It’s March 26, 2025, and I’m thinking about trans day of visibility (TDOV, March 31st). Part of me is thinking “please, no, I would like trans people to be less visible right now, thank you.” And, from a safety perspective, that’s probably a good gut instinct. But I also don’t know that it’s true that trans people and experiences are hyper-visible; transness as an idea is, as is an imaginary cabal of dangerous trans people preying on women and children. For years, bigots* have been crafting that mythical figure of transness to justify trans antagonism** (and it’s not just bigots anymore; even well-intentioned people who are convinced by the onslaught of anti-trans messaging perpetuate these myths).

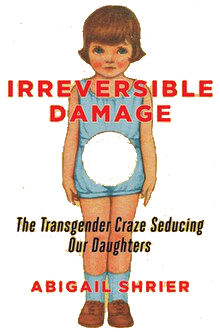

Some of that anti-trans messaging is obvious. We see it in books like Janice Raymond’s (1979) The Transsexual Empire and Abigal Shrier’s (2020) Irreversible Damage; on social media like J.K. Rowling’s tweets; in audiovisual media like the virulently anti-trans podcasts and videos created by The Daily Wire; and more (Contrapoints, 2021). Other examples are more nuanced (and, I think, scarier as a result). The New York Times’ disproportionate and sensationalizing coverage of “genital surgeries in adolescents” (Ghorayshi, 2022), “a small number of doctors” who oppose prescribing puberty blockers (Twohey and Jewett, 2022), and the “sharp rise in transgender young people” to a whopping “0.6 percent of the population” (Ghoryashi, 2022) are exemplary here. In these places and more, both “fringe” and mainstream media are making their version of (anti-)transness inescapable through selective omission, hyper-focusing on the most controversial issues and examples, carefully curated rhetoric, and, frankly, lies.

what would you put in your irreversible damage hole?

All that to say, this mythical trans villain feels ubiquitous. Moreover, it’s used to justify an onslaught of anti-trans legislation and Executive Orders,*** which then reinforce the myths that helped birth them as people see those bills/laws and Orders and think “if politicians are working this hard to fight the ‘woke trans agenda’ or whatever, then surely it must be dangerous.” But also, a lot of anti-trans media and politics insists that trans and non-binary people AREN’T EVEN REAL. As Executive Order 14168 (“Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism…”) declares, there are “two sexes, male and female. These sexes are not changeable and are grounded in fundamental and incontrovertible reality.” It’s like we’re somehow simultaneously all powerful and non-existent.

The Disenabling Effects of Anti-Trans Media

But where are trans people in all this? There’s so so so much media and policy about us, but actual trans human beings are conspicuously absent. As many of the people I interviewed for my dissertation research (on trans joy) pointed out, the result is a hegemonic narrative of transness as something bad or scary. Trans and non-trans people alike internalize that message. Participants described not being able to imagine a normal trans life for themselves, let alone a happy one. As one interview participant, Ernest (fake name), said, “transness is so often framed as this sort of condition of despair…it didn’t occur to me as an available step because…it was never framed as a joy or a relief to be trans” or transition.

This effect is a core aim of anti-trans legislative efforts. Bills such as those banning trans girls in school sports directly impact very few people, but they operate more broadly as part of an affective and legislative assault on trans life. Ernest continued:

aside from being…straightforwardly punitive, it seems like those kinds of laws also exist to be like ‘there will be no one for you [trans youth]. There is no network, you will not be able to have support.

The resulting isolation and anxiety are, as bell hooks (2000, 57) puts it, “absolutely disenabling.” In other words, anti-trans media and legislation are part of an affective politics that fosters fear and sadness in order to stultify trans liberation and the challenge it poses to the essentialist sex/gender binary and to various systems of power/oppression with which it’s intertwined. (I recognize that this is a big claim to just leave hanging, but it’s the end of March and I need to finish this zine. Important conversation for another time.)

That hegemonic narrative of transness as something to fear or hate operates in the service of intersecting modes of oppression in part by casting itself as inevitable. This is the way life is and must be, it asserts. Positive trans representation obviously challenges this hegemonic facade, as do portrayals of mundane trans lives. Just seeing trans people existing in the world, being “normal (or normally abnormal) people” (Duncombe, 1997, 23) with “normal (or normally abnormal)” lives, breaks through the noise of anti-transness. For example, another interview participant, Gerrard (also fake name), shared the following in response to the question “what comes into your mind when you hear the phrase ‘trans joy’?”:

I'm from Southern Ontario originally, which is very conservative. And something that gave me a lot of trans joy when I moved here to go to school is that there were like 8 trans people, just like fully out trans people, in my class. And I was like, “Oh, my God, like, you people exist. Like, there's more [of you/us].”… And like, I wasn't out at that time. And so they gave me the strength to like, come out and like, accept myself for who I am. Because I can see how happy they were living their lives. And yeah, it's just like, a very formative part of my life.

Seeing a small group of trans people happily “living their lives” empowered him to accept himself and build his own happy trans life.

Trans Visibility and QT Zines

Thought of in this way, QT (queer and trans) zines and perzines (short for personal zines) are a distinctly political form of trans visibility. After all, if the goal of anti-trans politics is to foreclose trans life, the windows QT (per)zines offer into the very real lives of very real trans people are a response. In other words, QT zines are one format through which we can disrupt hegemonic narratives of transness as negative by showcasing trans joy and trans mundanity (of course, they’re just one part of a broader participatory media**** landscape). At the same time, they offer a space for queer and trans people to reassert our agency, navigate the realities of our lives, and build connections (see “Dispatches from the Anarchist Lit Fair” later in this zine for more on that last point).

Amidst the simultaneous hyper-visibility and invisibility of mainstream trans representation, zines give us back agency. We’re visible in zines on our own terms. How we’re portrayed, who we share our stories with (to an extent), we decide. Actual trans people in all our particularities and multifaceted identities and experiences are absent in the hegemonic narrative of transness, but we’re very much present and accounted for in zines. And when trans people control our own narratives, the resulting media is often (but far from exclusively!) more quotidian and, as a result, more relatable than mainstream and far-right media. That it is mundane does not, however, mean it is any less political. There are literally thousands of examples I could use here, but let’s start with this one from issue 7 of Sol Brager’s zine Sassyfrass Circus (reproduced here from the Queer Zine Archive Project, archive.qzap.org):

Page 12 of Sassyrfrass Circus #7

Pages 15 and 16 of Sassyfrass Circus #7

In this piece, titled “Idiopathic Hirsutism,” Sol explores some of their feelings about their facial hair as (at the time) a queer woman/woman-adjacent person (Sol and I both later came out as trans). They talk about being probably misdiagnosed with PCOS (ovary-related condition that causes, among other things, “excess” body and facial hair), mixed feelings on laser hair removal, their mom’s response, and how all that connects back to embodied politics and “a politic of assimilation” (Brager, 2011, 15). It’s a window into the brain of “the fat hairy kid of a really Jewish mother” (16).

As a very hairy Jewish person whose “‘diagnosis’” was, like Brager’s, “more likely to be idiopathic hirsutism, which just means I’m hairy” (12), this piece stopped me in my tracks. I remember what it was like to be a queer “woman” with facial hair. I remember agonizing about what to do about it and feeling alone in that agonizing, but I hadn’t connected that to the politics of visibility and assimilation before. While I’ve since become far more comfortable with my facial hair, I still have to think about what to do about it as someone who is read as a woman more often than not. And I don’t know if it’s shame or social norms or whatever, but to this day I feel uncomfortable talking to people about my facial hair (this is me being vulnerable! the power of zines!). So, for the better part of a decade, I’ve just been alternating between avoiding thinking about a part of my literal face and trying to process my big feelings about it on my own.

Fast forward to reading this zine. Seeing my own experience reflected back in a QT zine made me feel less alone and inspired me to think about my facial hair in relation to my politics. Sol is offering a window into something that is ultimately one of many day-to-day decisions queer and trans people (and not queer/trans people in different ways!) navigate. Through that representation of the queer/trans mundane, they bring our attention back to the relatively unremarkable, embodied experience of queer and trans life. Moreover, in connecting that experience to more explicit political considerations, they demonstrate a version of QT politics that begins from our perspective. Compare that to the politics I described earlier sensationalizing the most controversial details of our lives.

Joyful Trans Media

Furthermore, there’s joy in actual QT life, and QT zines often showcase that in their portrayals of queerness/transness. This is a place where the medium of zines introduces distinct possibilities: including visual elements, side notes, jokes mixed into essays, and so on allows zinesters to include a joyful or humorous affective resonance when discussing both light-hearted and heavy subject matter. In the pages from Sassyfrass Circus from the last example, we see this in the drawing of Brager as “a goddamn unicorn” and funny inserted thoughts. It is a distinctly joyful piece, but it is also a serious discussion of an issue they’re facing and its connections to politics.

Another example from the popular zine A Guide to Cis-hetero Grooming Your Child takes this approach even further:

It takes the form of an illustrated “how-to” guide to ensuring your child will achieve cisgender normativity, from “Step 1: Decide their gender based on what you can see of their genitals” through “Step 4: Make sure over + over + over to take them to the right place to pee” (Neal, n.d.). It concludes with both pain and hope for queer and trans readers: “load it all up until they crack… and come out the other side,” which is to say, until they come into their own self-defined gender and sexuality (Neal, n.d.). If you were to pull the text out of this zine and present it with no further context, one misses its critique of the practices it describes. That’s because it uses comedic drawings and tongue-in-cheek phrasing and formatting to communicate the absurdity of cisnormative gendering practices in childrearing. At the same time, it is a relatable, funny critique for its primarily queer and trans audience, a group who largely experienced the practices described but clearly did not, in fact, grow up to be cis-hetero adults. It thereby connects their personal experiences—and those of children raised under strict binary gender norms in general—to a broader political project of reinforcing cisheteronormativity. In short, it launches an effective critique of cishetero gendered practices through an affective queer and trans joy.

Conclusion

There’s a lot more I could say here, but it’s now March 31, 2025, Trans Day of Visibility, time to release these thoughts into the world. So I’ll end with this: I think what I’m trying to say is that queer and trans (among other!) zines give us a forum to portray something of queer/trans ordinaries. It’s unremarkable trans visibility, and I think that’s what I’m looking for. In rendering queerness and transness unremarkable, QT zines open space for more interesting, messy, nuanced conversations about queer and trans life. And our lives are so, so much bigger and more beautiful than trans antagonism would have you believe.

Anyway, happy TDOV, I guess. I’m off to go celebrate with Dean Spade’s latest book and a latte the size of my head.

Notes

*There’s probably a more technically correct term for this, but I’m sick of masking bigotry with more palatable language.

**I picked up this term from Hil Malatino’s (2020) Trans Care. Trans Care BC (public health service in BC coordinating transgender healthcare) defines it as “another term for transphobia, which highlights how discrimination and violence against trans people does not usually come from a place of fear, but rather from ignorance, dislike, and hatred of gender diverse people” (TransCare BC, 2025).

***809 anti-trans bills have been introduced at the local, state, and national levels in the US this year as of March 27 (translegislation.com).

****In Girl Zines, Alison Piepmeier defines participatory media as “media created by consumers rather than by corporate culture industries” (2008, 2).

Sources and Further Reading

Brager, Sol. Sassyfrass Circus #7, 2011.

J.K. Rowling | ContraPoints, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7gDKbT_l2us.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. Haymarket Series. London : New York: Verso, 1997.

Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism And Restoring Biological Truth To The Federal Government, 14168 Executive Order § (2025).

Ghorayshi, Azeen. “More Trans Teens Are Choosing ‘Top Surgery.’” The New York Times, September 26, 2022, sec. Health. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/26/health/top-surgery-transgender-teenagers.html.

———. “Report Reveals Sharp Rise in Transgender Young People in the U.S.” The New York Times, June 10, 2022, sec. Science. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/10/science/transgender-teenagers-national-survey.html.

hooks, bell. All about Love: New Visions. New York: William Morrow, 2000.

Malatino, Hil. Trans Care. Forerunners: Ideas First. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Neal, Lawrence Lewis. A Guide to Cis-Hetero Grooming Your Child, n.d.

Piepmeier, Alison. Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. New York: NYU Press, 2009.

Tourmaline, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility. Critical Anthologies in Art and Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017.

Trans Care BC. “Glossary | Trans Care BC.” Accessed March 29, 2025. https://www.transcarebc.ca/glossary.

Twohey, Megan, and Christina Jewett. “They Paused Puberty, but Is There a Cost?” The New York Times, November 14, 2022, sec. Health. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/14/health/puberty-blockers-transgender.html.